- Home

- Diana Palmer

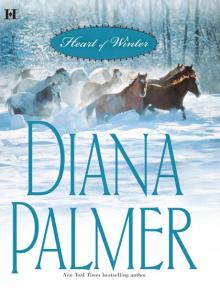

Heart of Winter Page 11

Heart of Winter Read online

Page 11

He eased his mouth away from Nicky’s, steeling himself not to care about the soft accusation in her drowsy eyes as she watched him pull away.

“Please…” she whispered, and made a move to go to him.

“No, thanks,” he said quietly. And the very tone of his voice halted her in her tracks. He was as politely indifferent as if he were refusing a drink of water when he wasn’t thirsty.

She looked up at him with slow comprehension. He didn’t even seem to be affected by that sweet interlude. He was just indifferent. She felt a sudden, sharp emptiness. Was this how it was going to be from now on? Was he so uninvolved that it didn’t require any effort for him to draw away from her? She’d banked everything on his desire for her; she’d seen it as her one way to reach him. But it hadn’t. She’d lost. He didn’t trust her. And now he was showing her that he didn’t even want her anymore.

“I’m not a gold digger,” she said with what pride she had left. She was trembling, and he had to know it. She wrapped her arms around herself and watched him, like a hurt child. “Money doesn’t matter to me. Surely you can see that?”

“I don’t know you,” he answered. His dark eyes narrowed as he studied her face. “And maybe it’s better this way. I remember telling you once that we could hurt each other badly. I let you get to me last night, honey, but I won’t make that mistake again. The last thing I want is involvement.”

“But you said…I mean, I thought…” she faltered, trying to put into words what she’d felt the night before, what she’d thought he meant.

“I’ve been alone a long time, daffodil,” he said with a mocking smile. “And I’m no saint. A man gets lonely from time to time.”

In other words, she’d been a nice little interlude with no strings attached, but now it was broad daylight and he’d come to his senses. He’d just proved his indifference by showing her that he could pull away from her anytime he wanted to without regret.

“That’s plain enough,” she said quietly, studying his dark, impassive face. It was a long way up, despite her own height, and she felt at a disadvantage. “I guess I misread the whole situation.”

“Just as long as you realize you’ll never get to first base around here, except in business. Get my drift?”

She should have pasted him one, but she was disillusioned and sick at heart. Her dreams were shattered. “I can’t really blame you for the way you feel,” she said dully. “I should have told you the truth in the beginning. I guess it was a hard knock.”

“Nothing I couldn’t handle,” he replied coolly. “Don’t flatter yourself too much. A few kisses doesn’t make a relationship.”

“Oh, I know that,” she laughed coldly. “And just for the record, I was lonely, too. You see, men haven’t noticed me for a long time; not since I had money, in fact,” she said with a cynicism that suddenly matched his. She felt old and world-weary and battered. “Too bad I can’t go home to Daddy and accept that trust my mother left me. That would up my bank balance by about three million.”

She went to the door and opened it, watching him scowl as her remark registered.

“Dream on, honey,” he said, but without a lot of conviction.

“You don’t believe that, either, of course,” she nodded. “Why don’t you ask my father why my fiancé threw me over? The answer might open your eyes.”

He stared at her for a long moment. “If you’ve got that kind of money, why work for my brother?”

“Because I got sick of a warped lifestyle where promiscuity and alcohol and pills seemed to replace love in my parents’ relationship! Because I got lost somewhere and went hungry for just a little love!” Tears welled up in her eyes and she set her lips together to try to stop the trembling. “The man I thought I loved walked out on me the day he found out I’d given up all that nice money. And here I am, two years later, being accused of the very thing he was guilty of. You think I’m mercenary,” she said in a husky whisper. She laughed tearfully. “How’s that for irony?”

He stopped in the doorway to look down at her. His conscience and his pride were at war. “You lied to me once, damn it!”

“So you can’t ever trust me again,” she returned. “Okay, you’ve judged me and found me guilty. I don’t want your pity. I don’t want you at all. My father was right all along—everybody’s got a price. I should go home with him and let him teach me how to buy people!”

“You’re talking nonsense,” he said curtly.

“I’m talking sense,” she said on a laugh, although her chin was trembling. “I’ve been chasing rainbows. Thanks for putting me back on the right track.”

“You’re crying,” he said half under his breath and lifted a hand to catch a stray tear.

But she jerked away from his hand like a wounded thing, raw from his rejection, sick at heart. “Go away,” she whispered furiously. “I hate you! I hate you, Winthrop! I wish I could leave here tomorrow and never have to see you again as long as I live!”

He tried to speak, but he couldn’t seem to find words. In the end he turned and stormed off down the hall, smoldering. He was the wronged party, so why in hell did he feel guilty? He didn’t even want to think about how he might have messed up things if she was telling the truth. Surely she wasn’t. She’d lied to him once, hadn’t she? He closed his mind tight. He just wouldn’t think about it. She was another Deanne. He was well rid of her.

She watched him go with a sore heart. Well, if he wouldn’t believe the truth when it was staring him in the face, who cared? She closed the door and gave up any idea of going downstairs again. She took off her clothes and cried herself to sleep.

Chapter Seven

Somehow, Nicky got through the night. Winthrop had excused himself and gone out to help his men keep a check on the cattle. The snow had made the mountain roads impassable except with a four-wheel drive. The hunters didn’t seem to mind. In fact, they were apparently used to mountain weather and since they were planning a week-long outing on the ranch, they settled in with easy acceptance.

Carol, however, became a pill. Nothing pleased her. Her room was too cold, the bed was lumpy, there were no shopping centers and she couldn’t even get a manicure. Furthermore, she missed her parents, whom she visited every few days. She wanted to go home.

Nicky’s father spent the better part of the second day, in between cleaning his hunting rifle and getting himself kitted out with the proper attire, calming down his playmate. It seemed he had a knack for communicating with Carol, because he finally got through to her that it would be impossible to get out until a chinook blew in. That could be any day, he’d added with careful insight.

Mary had already told Nicky that the snow could go on for days or even weeks, but Nicky wasn’t sharing that tidbit with the excitable redhead. After Dominic’s comforting statement, anyway, Carol went off into the living room and watched a popular science-fiction thriller until even Winthrop started to grow tired of the film.

At dawn on the third day, the hunters piled into Winthrop’s Jeep and headed down the valley. Gerald and Nicky worked alone in the study, leaving Carol to her science-fiction habit.

“I can’t tell you how sick I am of light sabers,” Nicky remarked after the sound became louder in the next room.

“Sure you can,” Gerald invited, leaning back in his chair. “Go ahead. Then I’ll tell you how sick I am of laser cannons. And then we’ll make silly faces in the mirror and see about renting straitjackets in a matched set.”

She giggled. “Let’s pray for a chinook.”

“I’m for that. The Sioux used to have a prayer for it, come to think of it. We’ll ask Mary.”

She looked at her steno pad. “Winthrop said something to her at breakfast with sign language. Mary’s been teaching me a little bit of signing, so I tried to watch carefully.”

“I watched for years and never learned a thing,” he confessed. “What did he say, do you know?”

She smiled ruefully. “Either he wanted bicarbonate of

soda or he was melancholy.”

He frowned. “What?”

“When you want to express melancholy or gloom, you make the sign for heart and then the sign for sick. It’s really a fascinating insight into another language,” she added. “For instance, if you want to say that you’re disgusted, you sign heart and then tired. The sign for enemy is friend and not. Drunk,” she grinned, “is expressed by making the signs for whiskey, to drink, much and mad. See?”

He shook his head. “Fascinating. Smart girl.”

“Intelligence is this,” she said, touching her right index and middle fingers to her forehead.

“How about smart aleck?” he taunted.

“I’m not that good, yet,” she sighed. But she was learning. Already, Mary had taught her enough that she could translate what Winthrop had “said” to her on the porch the morning he’d brought her home from the Todds’. He’d said that he was jealous of Gerald, and that he wanted her very much. How different things might have been if she’d known that at the time. But Winthrop had become a coolly considerate host and nothing more. All the lovely soft feeling that had been growing so gently between them was gone forever.

“I’m worried about Sadie and Mrs. Todd,” Gerald said abruptly, tapping a pencil on the blotter. “I tried to phone them an hour or so ago, and the lines are down. Sadie had to put their Jeep in the shop a couple of days ago, so I know they don’t have any transportation. I drove by there before the snow started, just to say hello.”

“Could you get Winthrop to run up and check on them?” she asked.

“Winthrop is in a snit lately, haven’t you noticed?” he asked miserably, his gaze apologetic as he added, “Your father did a job on your character. Although, to give the man credit, he tried to tell Winthrop it was mostly just bad temper and vengeance. But Winthrop didn’t listen. He walks off every time your name is mentioned.”

“We had an argument and didn’t exactly part friends,” she told him, without going into details. She didn’t add that Winthrop’s attitude had broken her heart. “You wouldn’t want to go back to Chicago anytime soon?” she added hopefully.

“Poor Nicky,” he said, smiling at her knowingly. “I’m sorry it turned out like this. In the beginning, Winthrop was so different when you were around. He smiled and laughed and seemed to enjoy life for the first time since the accident. I’m sorry it fell apart.”

“So am I,” she confessed, feeling her eyes sting with unshed tears. “I guess he’s soured on me because I didn’t tell him who my father was. He thinks I lied to him. And perhaps, in a sense, I did. But I didn’t mean to be devious. I was only trying to forget the past. My childhood was pretty rough, and my mother’s death shook me up. There are so many scars. I guess that’s why I understand Winthrop so well. I have scars, too, and time isn’t all that healing when your emotions have been ravaged.”

“I guess so.” He got up and went to the window. “I wondered why Winthrop was flirting with Carol. I supposed he was trying to make you jealous.”

“On the contrary,” she laughed, “he was showing me that I don’t matter. And believe me, he’s succeeded. I wouldn’t go near him now with a whip and a chair.”

“I can understand how you feel,” he said, turning. “But you have to understand how it’s been for my brother, Nicky. It was several months after the accident before he was even able to walk without a cane, and they’d threatened at first to take off the leg entirely. Winthrop said they’d take it off after he was dead, and he meant it, but he doesn’t realize even now how close it came to that. It took one of the best orthopedic surgeons in the country to save it—and he performed an operation that used techniques he invented as he went along. One of the bones in his lower leg was shattered; the surgeon completely rebuilt it, like putting a jigsaw puzzle together.”

“He said there were complications,” she probed.

“His impatience,” he said, confirming her suspicions. “They told him exactly what he could and couldn’t do, and he ignored them and tried to ride a horse the day after he came out of the hospital. He tore the cartilage and had to go back into surgery to have it resewn. Consequently it hasn’t healed as well as it could have. But the doctors said he could get rid of that limp if he’d work half as hard at his exercises as he’s worked at fighting them tooth and nail over the manner of his recovery. Winthrop,” he added dryly, “is impatient.”

As if she hadn’t already noticed that, she mused sadly. “I suppose at the time he didn’t much care what happened to him.”

“It was the closest I’ve ever seen him come to the edge,” Gerald agreed. “He took chances and pushed himself even harder than he used to in his wild days. Finally I asked him if the stupid woman was worth his life. And that seemed to snap him out of it. But he’s not the same man he was.”

“What was he like then?” she asked, because she wanted to know everything there was to know about him.

“Full of fun,” he said. “Reckless, with a devil-may-care attitude, but in a suave kind of way. He liked music and parties and skiing—in the water or in the snow. He was forever on the go. The ranch was important to him, but not in the way that it is now. He left Mike in charge and went out to beat the world. Now,” he said softly, “he just sits up here in the mountains and broods. Less since you’ve been here, I have to admit, but he still has that streak of melancholy.”

“Maybe he found out that money and glitter don’t wear well,” she said. “I learned it young.”

“Perhaps he did.” He studied her quietly for a long moment. “It hurts you that he believes your father, doesn’t it?”

“More than I can tell you.”

“Give him time, Nicky. Trust comes hard to a man who’s been betrayed. But if the feeling is there, inevitably it’s going to break through the ice.”

“Think so?” She smiled. “I wonder.”

They went back to work, but she brooded about what Gerald had said. Would Winthrop eventually come to his senses? Or had it been just a mild physical attraction and he wanted nothing more to do with her? She didn’t know.

Later that afternoon, Gerald began to pace, and rubbed his stomach as if it were troubling him.

“Need an antacid?” Nicky asked.

“What?” He glanced at his stomach. “Oh. It’s just acting up. I forgot my medicine. I guess I’d better take it. No, it isn’t that,” he said suddenly, turning. “I’m worried about Sadie.”

“Then let’s go see her. Isn’t there a four-wheel drive around here somewhere that we can use?”

He grinned. “Sure. Are you game? It could be dangerous.”

“I’d like some fresh air myself.” She glanced toward the living room door, where the sound of laser blasts was echoing loudly. “And I need a reprieve from that movie that I loved until we got snowed in with her.”

“My sentiments, exactly. I’ll tell Mary where we’re going. Dress warmly.”

Warmly meant putting on her jeans, two pair of socks, boots, a long-sleeved shirt, a sweater, and her heavy coat, gloves and a stocking cap. Even that was hardly enough against the thick snow and biting wind. The mountains were cold in November, she learned quickly. And the snow was flying at them in an unending sheet of white, provoked by a wild wind. Nicky had misgivings about this trip, but she had more about being cooped up inside with Carol.

Gerald had the old Jeep idling when Nicky climbed in beside him. She glanced around her with a curious smile. “Will it get us there?” she asked hesitantly.

“I hope so,” he confided. “It hasn’t been used for a while, but Mike has one and Winthrop has the other new one, so we’re stuck with this. I think it will be all right.”

The vehicle sputtered and lurched as he put it in gear, and the chains on the heavy tires made a nice clanking sound as he shot down the mountain road. Thank God it was a wide one, but by the time they turned off onto the dirt road that led up to the Todd place, Nicky was regretting her decision to go with him. Gerald wasn’t the driver Winth

rop was, and as the heavy snow continued to fly at them, Gerald swung too wide around a curve and the Jeep suddenly left the road.

Gerald moaned something. The Jeep lurched crazily sideways and slid down onto a lodgepole pine and hung there, shuddering. Nicky pitched against his shoulder, and got a sudden and terrifying view of a sheer drop out his window.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake!” she squeaked.

He caught his breath, staring beside him. “Damn,” he breathed. “I couldn’t see the roadbed and I ran right off. Nicky, we’ll have to get out of here. This is a dead pine, and if it gives way…” He glanced at her with pure terror in his dark eyes.

“Then we’ll get out,” she said, more calmly than she felt. “How?” she added.

“Well…” He studied the Jeep’s position for a minute. “I think it might be easier if we tried to get out on your side. The tree will balance us. You go first. I’ll help.”

Climbing out of the Jeep looked impossible, but there was no choice; plunging down that deep ravine would be as sure as death. She thought of Winthrop and wondered if he’d miss her if she pitched down there. Morbid thoughts, and she shook them off. No, sir, she wasn’t about to give him the satisfaction of dying.

With Gerald’s help, she managed to lever herself up to the passenger door and gingerly open it. The Jeep pitched a little, and she caught her breath and shuddered, certain that the end was near, but the vehicle remained fairly secure against the pine. She prayed as she caught hold of the opening and began to drag herself up and over. She got grease from the dirty undercarriage all over herself, but in the end, she managed to tumble out. Then she reached up to help Gerald, who managed the task with more deftness than she had.

They cleared the Jeep and collapsed onto the thick, soft snow, almost buried in it while they caught their breath. Behind them, the Jeep lay on its side against the tall pine, unmoving, despite the fierce wind.

A Cattleman's Honor

A Cattleman's Honor For Now and Forever

For Now and Forever Texas Proud and Circle of Gold

Texas Proud and Circle of Gold Marrying My Cowboy

Marrying My Cowboy Wyoming Heart

Wyoming Heart Christmas Kisses with My Cowboy

Christmas Kisses with My Cowboy Wyoming True

Wyoming True The Rancher's Wedding

The Rancher's Wedding Mercenary's Woman ; Outlawed!

Mercenary's Woman ; Outlawed! Long, Tall Texans: Stanton ; Long, Tall Texans: Garon

Long, Tall Texans: Stanton ; Long, Tall Texans: Garon Lawless

Lawless Blake

Blake Escapade

Escapade Fire Brand

Fire Brand Cattleman's Choice

Cattleman's Choice Mountain Man

Mountain Man Long, Tall and Tempted

Long, Tall and Tempted A Love Like This

A Love Like This Miss Greenhorn

Miss Greenhorn Magnolia

Magnolia Lord of the Desert

Lord of the Desert Wyoming Fierce

Wyoming Fierce True Colors

True Colors Calamity Mom

Calamity Mom The Pursuit

The Pursuit Rogue Stallion

Rogue Stallion Date with a Cowboy

Date with a Cowboy Heart of Winter

Heart of Winter Friends and Lovers

Friends and Lovers Love on Trial

Love on Trial Boss Man

Boss Man Callaghan's Bride

Callaghan's Bride Before Sunrise

Before Sunrise The Men of Medicine Ridge

The Men of Medicine Ridge Texas Proud

Texas Proud Wyoming Tough

Wyoming Tough Passion Flower

Passion Flower Maggie's Dad

Maggie's Dad Donavan

Donavan The Rancher & Heart of Stone

The Rancher & Heart of Stone Long, Tall Texans: Tom

Long, Tall Texans: Tom The Case of the Mesmerizing Boss

The Case of the Mesmerizing Boss Montana Mavericks Weddings

Montana Mavericks Weddings Redbird

Redbird Wyoming Strong

Wyoming Strong Darling Enemy

Darling Enemy Love by Proxy

Love by Proxy Coltrain's Proposal

Coltrain's Proposal The Best Is Yet to Come & Maternity Bride

The Best Is Yet to Come & Maternity Bride Rawhide and Lace

Rawhide and Lace Wyoming Rugged

Wyoming Rugged Patient Nurse

Patient Nurse Undaunted

Undaunted Long Tall Texans Series Book 13 - Redbird

Long Tall Texans Series Book 13 - Redbird Outsider

Outsider Long, Tall Texans: Drew

Long, Tall Texans: Drew Long, Tall Texans--Christopher

Long, Tall Texans--Christopher Merciless

Merciless A Match Made Under the Mistletoe

A Match Made Under the Mistletoe Evan

Evan Hunter

Hunter Now and Forever

Now and Forever Hard to Handle

Hard to Handle Amelia

Amelia Man of the Hour

Man of the Hour Invincible

Invincible The Maverick

The Maverick Long, Tall Texans--Guy

Long, Tall Texans--Guy Noelle

Noelle Enamored

Enamored The Best Is Yet to Come

The Best Is Yet to Come The Humbug Man

The Humbug Man Wyoming Brave

Wyoming Brave Calhoun

Calhoun Long, Tall Texans--Harden

Long, Tall Texans--Harden The Reluctant Father

The Reluctant Father Lawman

Lawman Long, Tall Texans: Hank & Ultimate Cowboy ; Long, Tall Texans: Hank

Long, Tall Texans: Hank & Ultimate Cowboy ; Long, Tall Texans: Hank Grant

Grant Nelson's Brand

Nelson's Brand Wyoming Legend

Wyoming Legend Diamond Spur

Diamond Spur That Burke Man

That Burke Man Wyoming Bold (Mills & Boon M&B)

Wyoming Bold (Mills & Boon M&B) Heartless

Heartless Long, Tall Texans--Luke

Long, Tall Texans--Luke To Have and to Hold

To Have and to Hold Once in Paris

Once in Paris A Husband for Christmas: Snow KissesLionhearted

A Husband for Christmas: Snow KissesLionhearted Night Fever

Night Fever Beloved

Beloved The Australian

The Australian Ethan

Ethan Long, Tall Texans: Jobe

Long, Tall Texans: Jobe Bound by Honor: Mercenary's WomanThe Winter Soldier

Bound by Honor: Mercenary's WomanThe Winter Soldier Tender Stranger

Tender Stranger After Midnight

After Midnight September Morning

September Morning To Wear His Ring

To Wear His Ring Heartbreaker

Heartbreaker Will of Steel

Will of Steel Dangerous

Dangerous Fit for a King

Fit for a King Diamond in the Rough

Diamond in the Rough Matt Caldwell: Texas Tycoon

Matt Caldwell: Texas Tycoon Iron Cowboy

Iron Cowboy Fire And Ice

Fire And Ice Long, Tall Texans--Quinn--A Single Dad Western Romance

Long, Tall Texans--Quinn--A Single Dad Western Romance Montana Mavericks, Books 1-4

Montana Mavericks, Books 1-4 Denim and Lace

Denim and Lace Eye of the Tiger

Eye of the Tiger The Princess Bride

The Princess Bride Long, Tall Texans: Rey ; Long, Tall Texans: Curtis ; A Man of Means ; Garden Cop

Long, Tall Texans: Rey ; Long, Tall Texans: Curtis ; A Man of Means ; Garden Cop Justin

Justin Nora

Nora The Morcai Battalion

The Morcai Battalion Heart of Stone

Heart of Stone The Morcai Battalion: The Recruit

The Morcai Battalion: The Recruit To Love and Cherish

To Love and Cherish Invictus

Invictus Regan's Pride

Regan's Pride A Man for All Seasons

A Man for All Seasons Sweet Enemy

Sweet Enemy Desperado

Desperado Lacy

Lacy The Winter Man

The Winter Man Diamond Girl

Diamond Girl Man of Ice

Man of Ice Reluctant Father

Reluctant Father Christmas with My Cowboy

Christmas with My Cowboy Love with a Long, Tall Texan

Love with a Long, Tall Texan Wyoming Bold wm-3

Wyoming Bold wm-3 King's Ransom

King's Ransom Christmas Cowboy

Christmas Cowboy Heart of Ice

Heart of Ice Fearless

Fearless Long, Tall Texans_Hank

Long, Tall Texans_Hank Unbridled

Unbridled Champagne Girl

Champagne Girl The Greatest Gift

The Greatest Gift Storm Over the Lake

Storm Over the Lake Sutton's Way

Sutton's Way Lionhearted

Lionhearted Renegade

Renegade Betrayed by Love

Betrayed by Love Dream's End

Dream's End All That Glitters

All That Glitters Hoodwinked

Hoodwinked Soldier of Fortune

Soldier of Fortune Rage of Passion

Rage of Passion Winter Roses

Winter Roses Rough Diamonds: Wyoming ToughDiamond in the Rough

Rough Diamonds: Wyoming ToughDiamond in the Rough Protector

Protector Emmett

Emmett True Blue

True Blue The Tender Stranger

The Tender Stranger Lone Star Winter

Lone Star Winter Man in Control

Man in Control The Rawhide Man

The Rawhide Man Untamed

Untamed Midnight Rider

Midnight Rider Trilby

Trilby A Long Tall Texan Summer

A Long Tall Texan Summer Tangled Destinies

Tangled Destinies LovePlay

LovePlay Blind Promises

Blind Promises Carrera's Bride

Carrera's Bride Calamity Mum

Calamity Mum Long, Tall Texan Legacy

Long, Tall Texan Legacy Bound by Honor

Bound by Honor Wyoming Winter--A Small-Town Christmas Romance

Wyoming Winter--A Small-Town Christmas Romance Mystery Man

Mystery Man Roomful of Roses

Roomful of Roses Defender

Defender Bound by a Promise

Bound by a Promise Paper Rose

Paper Rose If Winter Comes

If Winter Comes Circle of Gold

Circle of Gold Cattleman's Pride

Cattleman's Pride The Texas Ranger

The Texas Ranger Lady Love

Lady Love Unlikely Lover

Unlikely Lover A Man of Means

A Man of Means The Snow Man

The Snow Man The Case of the Missing Secretary

The Case of the Missing Secretary Harden

Harden Tough to Tame

Tough to Tame The Savage Heart

The Savage Heart